In 1987, Nikita Mikhalkov conceived an ambitious period melodrama set in the seldom-screened pre-twilight of the Russian monarchy, the reign of Aleksandr III (1881-94), a tsar whose natural lifespan and stable reign contrast sharply with those of his predecessor and heir, both of whom lost their lives to revolutionary politics. This was not Mikhalkov's first or last foray into period cinema (seven of his twelve features, in fact, are set between the 1880s and 1930s), but by the time The Barber of Siberia finally made it to the screen more than a decade after its conception, the particular period it depicts took on unforeseen significance in regard to the director's artistic and sociopolitical sensibilities. The setting serves as a reverse metaphor for the instability plaguing both Russian society and its film industry in the late Yeltsin era. Likewise, the protagonist's stalwart adherence to a national and personal code of values, Mikhalkov hoped, would attract Russian audiences back to theaters in a time of absent ideals and national malaise. Against the vibrant backdrop of Old Russia, Mikhalkov's costume melodrama gives full expression to his distinctive vision of the New Russia, and of cinema's role in it; he repeatedly characterized the film not as a portrayal of "how Russia is, but how it should be."

During the massive PR campaign surrounding Barber's February 1999 Kremlin premiere, observers pointed to such rhetoric–and even more so to Mikhalkov's cameo as the tsar himself–as evidence of the director's own presidential aspirations. His coyness regarding the will-he-or-won't-he-run question served to heighten the already stratospheric level of publicity for the movie. In addition to Hollywood-style media saturation, Barber was marketed using such tie-in products as vodka ("Russian Standard") cologne ("Cadet") and a custom-designed Hermes scarf. Thus, on both a diegetic and extra-diegetic level, Barber drew heavily on a reservoir of pre-Soviet, mercantile national images and values.

No less significant than the film's presumed ideological subtext is its position in recent Russian film history. Barber is a rebuttal of, and an intended antidote to, the trend in Russian film known as chernukha ("dark naturalism"), a pejorative term for the bleak, gratuitously violent, low-budget, and largely inaccessible films that had dominated the moribund domestic film industry for a decade. Mikhalkov's film is an almost programmatic anti-chernukha text. It has exquisite production value and offers an aggressively coherent narrative, which itself includes within it several events with their own narrative structures: a ball, a Shrovetide celebration, an opera. Well-placed outbursts of irrational, spontaneous behavior are acceptable (this is melodrama, after all), but they are impeccably motivated by a plot as disciplined as its military protagonist.

Mikhalkov's Barber, both as a work of art and an illuminated page in

the history of post-Soviet cultural politics, represents a mixture of impeccable

professionalism, unapologetic nationalism, and shrewd internationalism. It is a

singular example of Russian cinematic will-to-power firing on all cylinders.

–Seth Graham

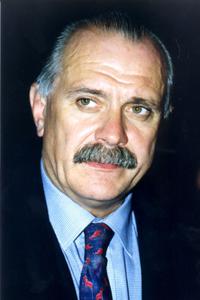

Nikita Sergeevich Mikhalkov was arguably already the most prominent and influential figure in the Russian film industry when he was elected chairman of the Russian Filmmakers' Union in May 1998, a post he still holds. He is the progeny of both the pre-Soviet cultural elite (painter Vasilii Surikov was his great-grandfather) and the Soviet nomenklatura (his father, Sergei, wrote the lyrics to the Soviet national anthem in 1944, and was recently recruited to do the same for the new, Russian anthem, set to the same music). His older brother is director Andrei Konchalovskii, and all three of his children are film actors (with roles in Barber, in fact). Mikhalkov has worn many hats within the cinema world–actor (he is a People's Artist of Russia), director, producer, screenwriter, teacher–and has served as advisor to the Russian Prime Minister on cultural issues, on the UNESCO commission for cultural development, and as chair of the Russian Cultural Foundation. His next film will reportedly be a sequel to Burnt by the Sun set during WWII.

| 1974 | At Home Among Strangers, A Stranger At Home |

| 1976 | Slave of Love |

| 1977 | Unfinished Piece for Player Piano |

| 1979 | A Few Days in the Life of I.I. Oblomov |

| 1979 | Five Evenings |

| 1981 | Kinfolk |

| 1983 | Without Witnesses |

| 1987 | Dark Eyes |

| 1990 | Hitchhiking |

| 1991 | Urga: Territory of Love (a.k.a. Close to Eden) |

| 1993 | Anna: From Six Till Eighteen (documentary) |

| 1994 | Burnt by the Sun (Oscar for Best Foreign Film) |

| 1998 | Barber of Siberia |